Beyond The Headlines

IN INVESTING, BEING RIGHT IS NOT ENOUGH: THE OTHERS MUST BE WRONG

We question some “certainties” held by the investing majority because, as Mark Twain said:

“It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble.

It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

* * *

In recent months, we have revisited the performances of some of our accounts as well as those of a few other portfolios managed by highly successful long-term investors. The periods under review ran between 20 years and 40-plus years: anything shorter would not include enough cycles to be instructive and anything longer, unfortunately, tends to be scarce.

Our aim was to try and distillate some wisdom about how long-term performance is achieved and, especially, to dispel some widespread assumptions or preconceived ideas that may lead us to use less-than-optimal tools and techniques for achieving it.

Being Right Is Not the Same as Building a Fortune

One of our favorite titles for an investment book, is Being Right or Making Money, first published in 1991 by Ned Davis Research, which tests and publishes a wide array of economic and financial indicators and tools for managing risks and making money.

We particularly like the contrast Davis’ book draws between being right and making money: The two are usually assumed to go hand in hand but, in fact, they often represent very different outcomes of the research and investment process.

Investment markets are auction markets, where companies’ fundamentals and investors’ emotions are constantly interacting in intricate and, at times, seemingly contradictory ways.

For example, after a company’s stock has risen for an extended period on a string of good results, its price reflects not only all its measurable qualities, but also investors’ psychological extrapolation of future progress. Then, unless the company’s fundamentals keep improving faster than anticipated, its stock’s potential to rise further is limited. On the other hand, any shortfall from investors’ growing exuberance may cause significant corrections. This asymmetry is why a good company does not necessarily make a good investment.

Beyond that, being right implies a closure marking the end of a finite period after which a new bet must be made to follow the preceding one. Building wealth, in contrast, does not imply any time limit and refers instead to a continuous process relying on the long-term magic of compounding.

Compounding consists of reinvesting income (interest or gains), rather than paying it out as realized, thus actually earning income on past income. It has been praised as a source of wealth creation by such iconic investors as Warren Buffett and Peter Lynch, but it also reportedly inspired scientists like Albert Einstein, who once said: “Compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world. He who understands it, earns it … he who doesn’t … pays it.”

Much of the difference between being right on the stock market and building a fortune in it thus depends on an investor’s time horizons. Personally, we find analyzing investment performance over shorter periods of time, even several years as do consultants, most media and many fiduciaries, irrelevant to wealth-building and much more akin to some competitive sports or games: good for immediate excitement, but not for value-creation.

Great Long-Term Wealth Builders Have Experienced Bad Years

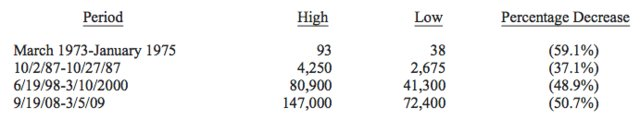

Another fundamental realization was that most successful, long-term wealth builders have endured periods of significant underperformance or even severe losses, as illustrated by the following table of Warren Buffet’s losing stretches, borrowed from Business Insider (2/24/2018):

Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway – Truly Major Dips

Referring to these episodes, the Oracle of Omaha himself stated: “Unless you can watch your stock holding decline by 50% without becoming panic-stricken, you should not be in the stock market.” And it is a fact that, despite these periodic, huge losses, Warren Buffett has been one of the greatest wealth builders of all time – over the long run.

This snapshot fits neatly into the ongoing debate about risk and volatility. Most consultants and theoreticians would assume that the kind of volatility depicted in the table above was the result of accepting too much risk in the quest for performance.

Successful wealth builders would answer that volatility is not risk, which implies the possibility of permanently losing one’s capital. This is unlikely if one feels confident about the conclusions of one’s analyses, exercises patience and shows character. In fact, with these qualities and adequate cash reserves, volatility can be viewed as an opportunity rather than as a risk, since it allows the owner to invest “when there is blood in the streets”, as the advice goes.

Absolute vs. Relative Returns

In recent years, with the proliferation of handlers of OPM (Other People’s Money), the emphasis in money management has shifted from absolute returns to relative performance.

It is perfectly understandable that operators or even fiduciaries that compete for market share in that universe need to shorten the performance-measurement periods even if this makes them less relevant to wealth-building. “I’ll measure your investment performance over the long-term and report to you every ten years” lacks the decision-making urgency which would appeal to most of today’s financial marketing departments.

Yet, it remains that wealth builders and owners are (or should be) interested primarily in the absolute returns (the end-results) generated by their assets, rather than by the interim scores achieved on the way, which are the main subject of relative-performance measurement.

Perverse Passivity

So-called active investing is primarily concerned with selecting individual securities in the hope of outperforming benchmark indexes, whereas passive investing consists of investing mostly in products that mimic leading indexes – as a way of approaching those indexes’ performances, an elusive achievement for a majority of investors.

Unfortunately, most leading indexes are “weighted”, which means that companies with the highest total stock-market values carry the greatest weights in the indexes. When a market or a sector becomes fashionable with investors, the corresponding index goes up and the manager of a portfolio mimicking that index is mandated to add to the portfolio’s individual positions — particularly those already carrying the greatest weight in the index.

The danger of automatically buying stocks as they become more popular – e.g. more expensive – is that they will suffer most when the market psychology changes and overall liquidity shrinks.

So, contrary to the label’s implication, passive investing is not really passive but, instead, transforms portfolio managers into momentum investors and even momentum amplifiers. It also does not allow for building cash buffers to take advantage of unusual opportunities when they arise.

A distinctive decision of active vs. passive management is to not invest when conditions are deemed inadequate and thus to occasionally build significant cash reserves. But…

The Main Benefit of Cash Reserves Is Not to Protect from Market Declines

It is generally assumed that holding significant cash reserves while markets are declining protects portfolios against bear market losses. And it does, mathematically: if the stock market goes down 40% and the portion of your portfolio invested in stocks is 70%, your portfolio will decline by “only” 28%. If, additionally, you are a successful value investor, it is possible that the portion of your portfolio invested in stocks will decline less than the market because it was undervalued to start with.

These assumptions are generally verified over time: value investors tend to underperform during phases of upward market momentum and irrational exuberance but, because they normally invest less as cheap buying opportunities dry up, they tend to build up cash reserves which help them outperform the markets when prices go down.

A closer examination of the portfolios we surveyed did show a tendency of cash-rich portfolios to outperform slightly during declining markets. But more striking was the very significant outperformance of many during the couple of years of recovery after the declines.

Upon reflection, this made sense, too. If you hold cash while a majority of stocks are declining from overvalued prices to undervalued ones, you are in a position to buy aggressively when stocks approach compellingly low prices and to fully benefit from the initial post-decline bounce. Of course, fully-invested managers will also see their portfolio bounce but remember: it takes a 100% gain to recover a 50% loss. [You start with $100. You lose 50% to $50. You then must double to return to $100.]

Fish from an Empty Barrel?

In recent weeks, our regular Sicart research meetings have generated more investment ideas than in the last couple of years, at valuations not too distant from levels where we might start buying shares in earnest.

Since we have been careful not to deplete our cash reserves with the stock market hovering near an all-time high, we questioned what had changed to generate such opportunities. Upon further investigation, we unearthed the following facts:

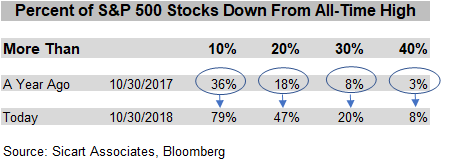

As recently as a year ago, the market’s overall volatility was at a record low, with most stocks close to their all-time highs. Today, we are seeing 3-4% moves in opposite directions day after day, sometimes within a single day. And the number of stocks that are down 10%, 20%, 30%, 40% from their all-time highs has more than doubled in the last 12 months.

A stealth bear market seems to have been developing, obscured by rotating exuberance in groups such as the notorious and capitalization-heavy FAANGS (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, Google), now correcting, and a number of other niches with superior growth — real or hoped for.

The Great Minsky Experiment

Economist Hyman Minsky hypothesized that crashes do not need a specific trigger because they are a phenomenon inherent to the capitalist system — a parallel with Marx that made him suspect to the profession until the 2007-2008 debacle. According to Minsky, stability feeds instability: the longer things stay stable, the more businessmen and investors become willing to ignore risk and become reckless – usually through a massive increase in the use of financial leverage (borrowing).

Whether they burst of their own pressure, or they are bared by the disappearance of liquidity (the ability to refinance), debt bubbles are thus the main source of recurring financial crises and recessions. Unfortunately, there is little in the theory that helps foresee when the bubble will burst – only that the more we inflate it, the closer we get to the bursting.

Not surprisingly, borrowers seldom acknowledge that they are undertaking more risk and the prelude to bubble bursting often looks like mere complacency rather than like outright speculation. We believe this is the case today.

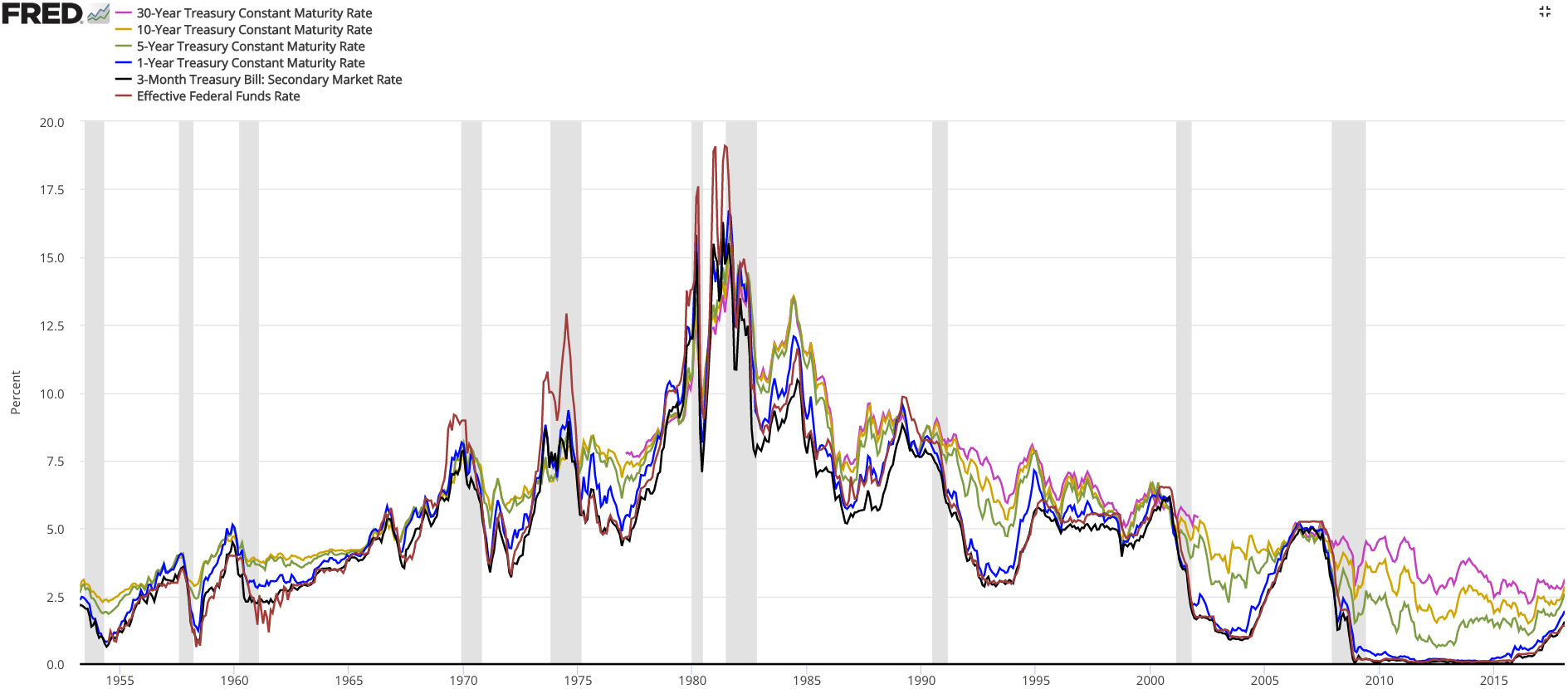

Back in the early 1980s, US interest rates for various maturities reached between 15% and 18%; they currently hover between zero and 5% as a result of quantitative easing and other interest-rate restraining policies by leading central banks.

We believe that observers tend to underestimate the massive changes that have taken place in the perception of risk by consumers, businesses, investors and governments over the last nearly 40 years of declining and then repressed interest rates.

One example of this recurring loss of investor memory is that Argentina, which had defaulted on its debt seven times in the past 200 years and three times in the past 23 years, was nevertheless able to sell to the public in June of 2017 almost $3 billion of bonds with a 100-year maturity. Not too surprisingly, with the country now in the midst of a major currency crisis, the bonds have already lost more than 20% of their value in a matter of 12 months.

Another example of investor amnesia is the relationship between interest rates and the US Federal budget deficit. According to the New York Times of September 25, 2018: “Already the fastest-growing major government expense, the cost of interest is on track to hit $390 billion next year, nearly 50 percent more than in 2017, according to the Congressional Budget Office. The federal government could soon pay more in interest on its debt than it spends on the military, Medicaid or children’s programs.”

Government borrowing is supposed to be countercyclical – expanding during recessions and declining during recoveries. But the US economy has now fully recovered from the Great Recession of 2007-2008 and yet the deficit is soaring, meaning that the stimulus is pro-cyclical, and that the government will have less room to maneuver when the economy slows.

As government spending, deficit and debt soared, in recent years, the cost of servicing (paying interest on) that debt did not increase proportionally because the Federal Reserve suppressed the cost of money by keeping interest rates artificially very low. Now, any inkling that interest rates might “normalize” at higher levels threatens to trigger a panic revision of future deficits upward. But until that happens, complacency reigns.

In a related set of assumptions, a number of observers have begun to worry that higher US interest rates might strengthen the US dollar and that the combination of a stronger dollar and higher interest rates might make it very difficult for emerging countries to repay the dollars they borrowed heavily during the most recent crisis.

We believe that we are currently in the midst of one of the long periods when Minsky saw apparent stability feeding instability. The results, when they become apparent may be described as “Black Swans” – rare and destructive events that could not have been anticipated. But one observer remarked that they could not have been anticipated mostly by those who did not want to look for them.

Where to next…

If not for a last-minute rally, October would have ranked among one of the worst months in global equity markets since the 2008/2009 financial crisis. We believe it may soon prove to be only an early preview of what may follow.

We have no way of knowing if that leads to a prolonged major sell-off or a series of more erratic price declines in various segments of the market, while the overall indexes remain range-bound trading sideways. Our patient, focused, disciplined approach prepares us well for both.

On one hand, we are keeping higher cash levels ready to deploy, and compelling opportunities are already starting to appear, on the other hand, we consciously continue to avoid potentially highly risky investments in the winners of the last few years.

François Sicart & Bogumil Baranowski

Disclosure:

This article is not intended to be a client‐specific suitability analysis or recommendation, an offer to participate in any investment, or a recommendation to buy, hold or sell securities. Do not use this report as the sole basis for investment decisions. Do not select an asset class or investment product based on performance alone. Consider all relevant information, including your existing portfolio, investment objectives, risk tolerance, liquidity needs and investment time horizon. This report is for general informational purposes only and is not intended to predict or guarantee the future performance of any individual security, market sector or the markets generally.