Beyond The Headlines

DANGER FOR THE 20%

The asset bull market of the last eight years has been quite comfortable for the 20% of the population who own investment portfolios. This is no time for complacency, however.

According to Bloomberg.com, a luxury condo on “Billionaires’ Row,” across the street from our office, is scheduled for a July foreclosure auction that might be the biggest in New York City residential history.

A shell company bought the condo in December 2014 for $50.9 million and took out a $35.3 million mortgage from a Luxembourg private bank in September 2015. Since the loan was not repaid one year later, when it was due, the bank is forcing a sale to recoup the funds, plus interest.

This news brings a few remarks to mind:

First and foremost, I am reminded of the high risk of investing with borrowed money. If our unfortunate billionaire across the street cannot sell his condo for more than $35.3 million dollars (and who can assess the true worth of a condo?), he will have lost his entire investment.

Second, people like us might have thought that we were comparatively rich – even part of the fabled “one percent.” But we are nowhere near the really rich who can afford the condos on “Billionaires’ Row.” These truly wealthy individuals are often foreigners. Some are American entrepreneurs who recently floated their startups on the stock market, others are those entrepreneurs’ investment bankers or and a few finance-related operators who have closed a major deal or received an exceptionally large special bonus. No one whose lifestyle depends on a salary or another traditional form of income can join the club of the truly rich.

My third point, however, is that the last eight years have been characterized by a steady upward run in stock and bond prices. As a result, (and this is often overlooked), life has been surprisingly comfortable for the relatively small segment of the population that directly owns investment portfolios.

Who are we, the investors?

In “The Dwindling Taxable Share of U.S. Corporate Stock” (taxpolicycenter.org, May 16, 2016), Steven Rosenthal and Lydia Austin reckon that there is $22.8 trillion in stock outstanding in the USA. (1)

Of this total, retirement accounts such as IRAs and pension plans own roughly 37%. Since most of these tax-deferred accounts will not be spent until retirement, I assume that they do not affect Americans’ perception of their current standard of living.

Meanwhile, the authors find that the amount of stock directly owned by individual investors (including taxable funds) has dropped from 80% in 1965 to only about 25% in 2015.

The danger is that the shrinking minority of investment-portfolio owners is increasingly viewed by today’s voters as a privileged elite not representative of the overall electorate.

Future elections may not favor investors

A majority of Americans in the lower income brackets admire high-earnings sports and entertainment stars, as well as ultra-rich business moguls. This was illustrated most recently by the election of Donald Trump to the U.S. presidency.

However, while the visibly, even ostensibly very rich do not seem to attract popular resentment, the story may be different for the merely rich.

NPR’s Steve Inskeep recently reviewed a new book, Dream Hoarders, by Richard Reeves, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. The author argues that the top 20 percent of Americans — those with six-figure incomes and above — dominate the best schools, live in the best-located homes and pass on the best futures to their kids:

“We protect our neighborhoods, we hoard housing wealth, we also monopolize selective higher education and then we hand out internships and work opportunities on the basis of the social network.”

According to Reeves, the American upper-middle class is essentially “hoarding the American dream.”

The perception is that the American upper-middle class is making out pretty well from current trends and that it is increasingly detached – occupationally, residentially, educationally and economically — from the rest of society. The fact that its members are not only separate but unaware of the degree to which the system works in their favor strikes Reeves “as one of the most dangerous political facts of our time.”

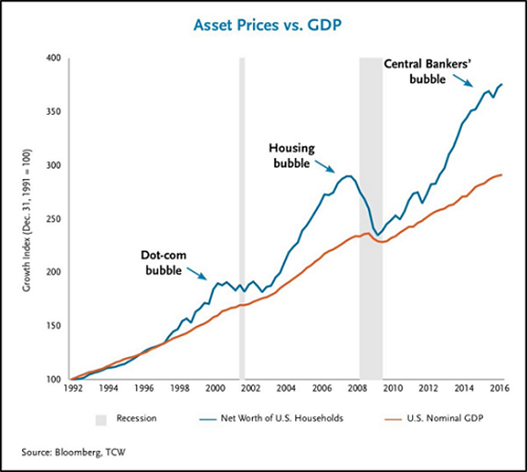

This is why, although the world’s economic and financial situation has remained worrisome for most, investors should not forget that they have had it pretty good for the eight years since the last financial crisis and so-called “Great Recession.” My partner Bogumil Baranowski reminds me that the net worth of U.S. households fell from a pre-recession peak of $67 trillion to $54 trillion in the midst of the recession, only to recover to $95 trillion today. This adds up to $40 trillion wealth creation from real estate and securities in the past eight years, mostly for the benefit of the upper middle-class.

A Judeo-Christian view of the stock market

My father, who was anything but a religious person, nevertheless taught me that, eventually, we are all rewarded or punished for our actions.

In most cultures, the bad deeds are fairly easy to recognize and are usually explicitly identified by laws or rules of good conduct. But even if we personally stay out of trouble, we may be guilty “by inaction” — allowing other individuals or groups to misbehave, out of complacency, moral myopia or mere denial. In the Judeo-Christian tradition, this complacency is complicated by the notion of guilt – in particular when you allow dubious things to happen that you might subconsciously enjoy or benefit from.

Maybe it is my heritage, or simply my innate contrarian bias, but I also always feel that when things go too well in the economy or the stock market, we do not fully deserve these good times, and we ultimately will have to pay for them.

Currently, the length of the global stock markets’ advances since 2009 puts me on alert, along with:

–the excesses I observe in debt use

–financial risk acceptance under the umbrella of record-low interest rates

–central bank inflationary or bubble-creating policies

–historically-high asset price valuations

–and finally, the complacency of most investors toward these excesses, which make me think, “Beware the day of reckoning!”

ASSETS DECOUPLING FROM INCOME SIGNAL FINANCIAL DANGER

Source: Bloomberg, TCW.

Investing like ostriches

Ostrich syndrome: “Denying or refusing to acknowledge something that is blatantly obvious as if your head were in the sand like an ostrich” (urbandictionary.com). This definition could be a Wall Street sage’s description of current investor sentiment.

One way to play the ostrich is to rationalize whatever the markets do, in an attempt to make it look logical and credible.

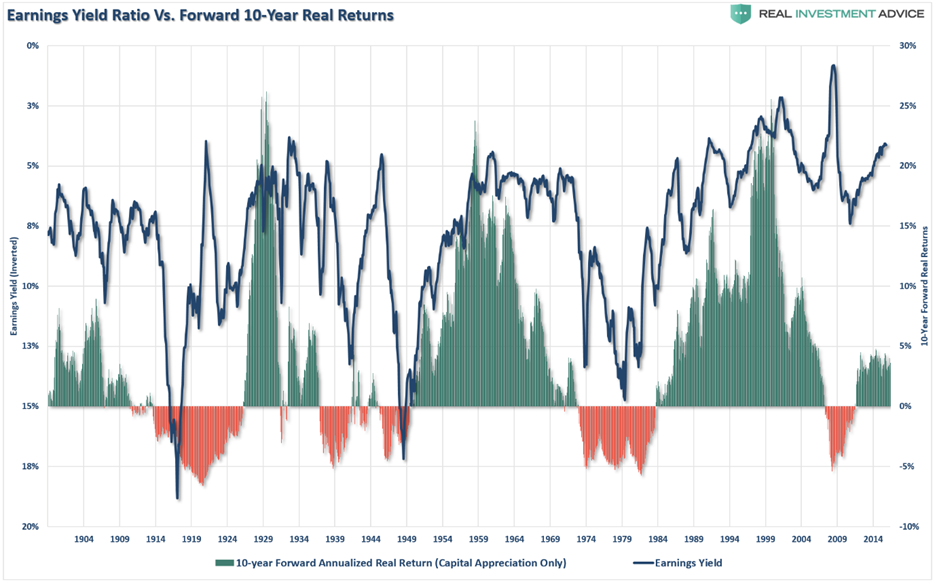

The Fed Model promoted by former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan basically states that when the earnings yield on stocks (earnings divided by price) is higher than the yield on Treasury bonds, you should own stocks. Many of today’s rationalizers use versions of this model to argue that investors should disregard current overvaluations and continue to chase stocks up, because interest rates are historically extra-low (in fact, negative in some countries).

In a 2003 critique of the Fed Model, Cliff Asness, a founder of AQR Capital Management and pioneer of quantitative asset management, criticizes pundits who illustrate (with a graph or a table) that P/Es and interest rates move together, and who then jump to the conclusion that they have proven that these measures should move together. In this view, which Asness challenges, investors are thus safe buying stocks at a very high market P/E when nominal interest rates are low.

Separately, economist Lance Roberts illustrates that what these pundits really should say is that it WAS a good time to buy stocks ten years ago (May 18, 2017 post, realinvestmentadvice.com). As shown in the chart below, which compares earnings yield (E/P: inverse of the P/E ratio) to following 10-year real returns, when the earnings yield has been near current levels, the return over the following 10-years has been quite dismal.

Source: Real Investment Advice.

For my part, I will just point out that, yes, interest rates have been declining for almost 40 years and are now near all-time lows. But in a cyclical world, low interest rates today foreshadow rising rates in the future.

Reformed Pundits

Even some of the pundits are beginning to worry about prevailing investor complacency. Rob Arnott is the founder and chairman of Research Affiliates. He has pioneered several modern portfolio strategies that are now widely applied, including tactical asset allocation, global tactical asset allocation, and the Fundamental Index approach to investing. With regard to Smart Beta, one of the most fashionable quantitative investment disciplines of recent years, the Research Affiliates website even claims that: “Clearly, Research Affiliates was offering investors smart beta strategies long before the term smart beta even existed.”

In February 2016, however, Arnott published with three colleagues a new paper: “How Can Smart Beta Go Horribly Wrong?”

The authors propose that the reassuring message of smart beta proliferators has two primary and interrelated flaws:

First, many of these… claims are based on a 10 to 15-year backtest that won’t cover more than a couple of market cycles. Second, such a short time span is very vulnerable to distortion from changing valuations. Our analysis shows that valuation has been a large driver of smart beta returns over the short and even long term. How much can we reasonably expect in future returns from these factors and strategies, net of valuation change?

Generally speaking, normal factor returns, net of changes in valuation levels, are much lower than recent returns suggest… If rising valuation levels account for most of a factor’s historical excess return, that excess return may not be sustainable in the future; indeed, our evidence suggests that mean reversion could wreak havoc in the world of smart beta. Many practitioners and their clients will not feel particularly “smart” if this forecast comes to pass.

Risk myopia

Michael Lewis’ Liar’s Poker (WW Norton & Company, 1989) is considered one of the books that defined Wall Street during the 1980s. The book is a semi-autobiographic, unflattering portrayal of Wall Street traders and salesmen, their personalities, their work practices and their ethics. However, six months after Liar’s Poker was published, Lewis reports finding himself “knee-deep in letters from students at Ohio State University who wanted to know if I had any other secrets to share about Wall Street. They’d read my book as a how-to manual” (Prologue to The Big Short 2010 – W.W. Norton & Co.)

Obviously, not everyone on Wall Street is crooked or unethical. But there is little doubt that, knowingly or not, many of its influential leaders and innovators are prone to take outsized risks with other people’s money. And, since “other people” is us, we owe it to ourselves to avoid playing the ostriches.

As early as March 26, 2014 Bloomberg.com quoted investor Seth Klarman as saying: “Giddy investors are living an existence where, on the surface, everything seems idyllic. In reality, the manufactured calm — thanks to the free-money policies of Ben Bernanke, Janet Yellen and Mario Draghi — anesthetizes us to the looming trouble. The longer QE continues, the more bloated the Fed balance sheet and the greater the risk from any unwinding.”

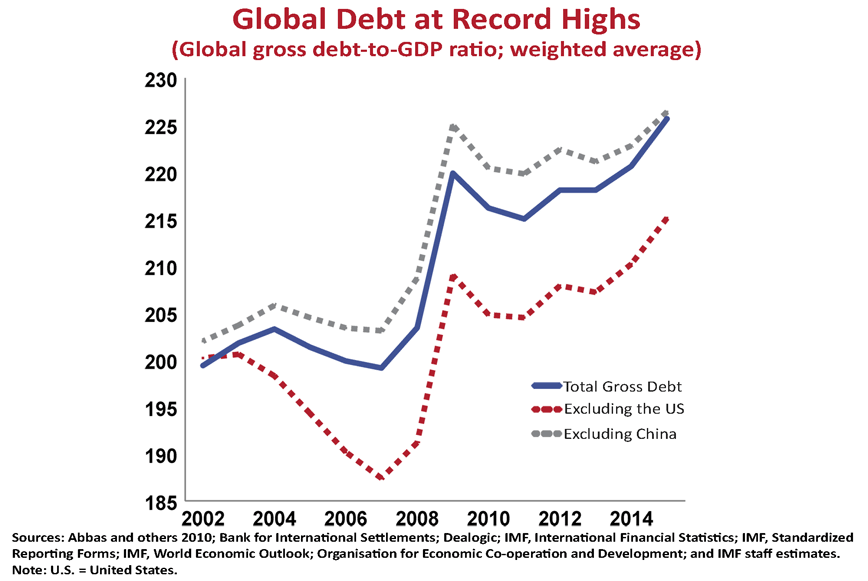

This is a stark reminder of economy professor Hyman Minsky’s warning that financial crises tend to arise naturally (without a necessary outside trigger) when a long period of stability and complacency eventually leads to the buildup of excess debt and overleveraging.

Source: Abbas and others 2010: Bank of International Settlements; Dealogic, IMF, OECD.

To try and quantify the stock market risk, I turn to John Hussman, in the Hussman Funds letter of June 26, 2017:

On the basis of the most reliable valuation measures we identify (those most tightly correlated with actual subsequent 10-12-year S&P 500 total returns), current market valuations stand about 140-165% above historical norms. No market cycle in history, even those prior to the mid-1960s when interest rates were similarly low, has failed to bring valuations within 25% of these norms, or lower, over the completion of the market cycle. On a 12-year horizon, we project likely S&P 500 nominal total returns averaging close to zero, with the likelihood of an interim market loss on the order of 50-60% over the completion of the current cycle.

Granted, Hussman has been cautious-to-negative about the stock market long enough to acquire the identity of a perma-bear. But he is also one of the experts who has thoroughly studied the correlation between various levels of stock market valuations and future multi-year returns.

We cannot forecast the timing of the next “Minsky moment” but we should keep in mind that, based on history, it could be painful.

François Sicart

6/27/2017

- Not including U.S. ownership of foreign stock and stock owned by “pass-through entities” such as exchange-traded funds.

Disclosure: This report is not intended to be a client‐specific suitability analysis or recommendation, an offer to participate in any investment, or a recommendation to buy, hold or sell securities. Do not use this report as the sole basis for investment decisions. Do not select an asset class or investment product based on performance alone. Consider all relevant information, including your existing portfolio, investment objectives, risk tolerance, liquidity needs and investment time horizon. This report is for general informational purposes only and is not intended to predict or guarantee the future performance of any individual security, market sector or the markets generally.